Of 20 Times More Wealth Between the Average White Family and the Average Black Family

September 28, 2020

Disparities in Wealth past Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances

Neil Bhutta, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne W. Hsu with aid from Julia Hewitt1

New data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) show that long-standing and substantial wealth disparities between families in different racial and ethnic groups were little changed since the last survey in 2016; the typical White family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family unit.

This FEDS Note explores patterns in wealth property by race and ethnicity, as well as some key issues related to the accumulation of wealth, using new data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). We first analyze full wealth among families classified, co-ordinate to their self-identification during the interview, every bit White non-Hispanic, Black or African American non-Hispanic, Hispanic or Latino, and other or multiple race (we will henceforth refer to these groups as White, Black, Hispanic, and other, respectively).two Wealth is defined as the difference between families' gross assets and their liabilities.3 We volition describe patterns at the median (the typical household within each group) and at the mean (the average among households in each group).

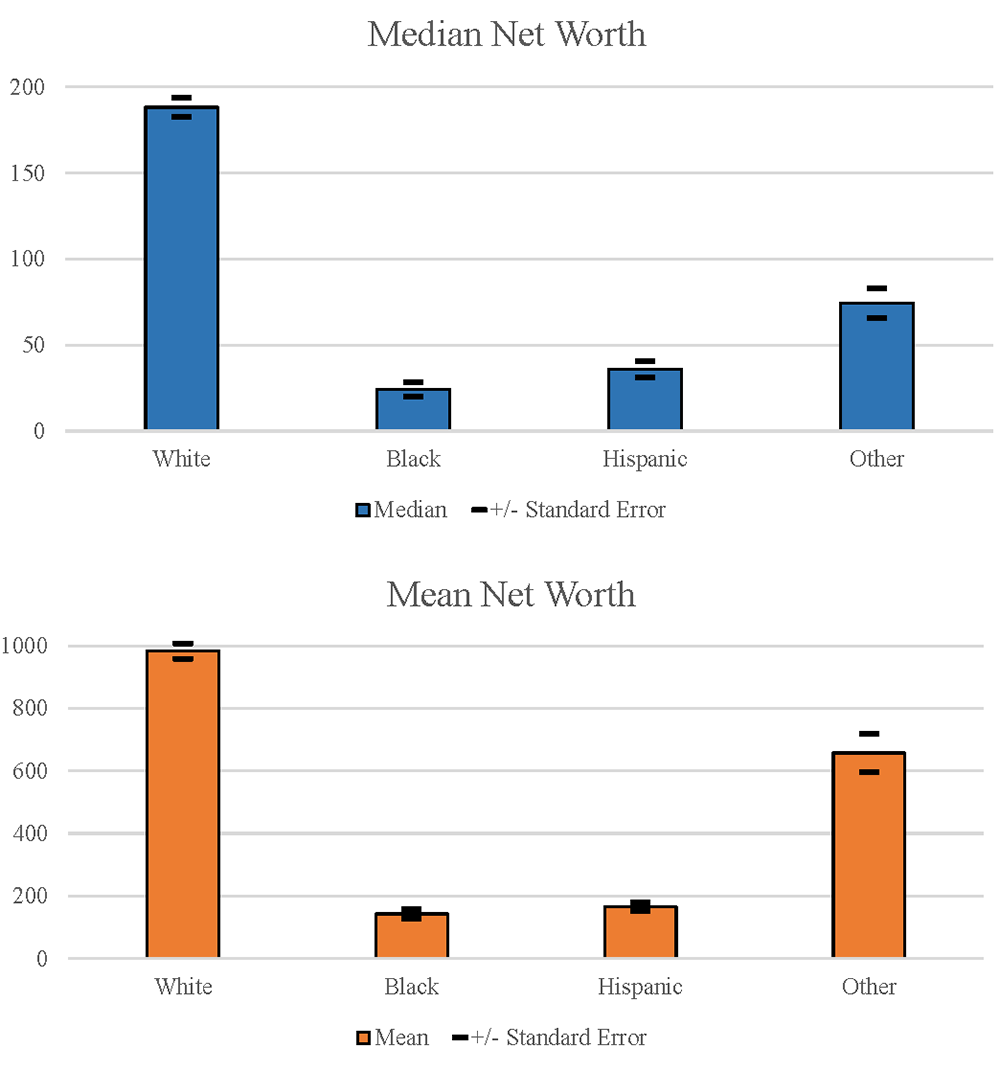

In the 2019 survey, White families have the highest level of both median and hateful family wealth: $188,200 and $983,400, respectively (Figure 1). Black and Hispanic families have considerably less wealth than White families. Blackness families' median and mean wealth is less than xv percent that of White families, at $24,100 and $142,500, respectively. Hispanic families' median and mean wealth is $36,100 and $165,500, respectively. Other families—a diverse group that includes those identifying equally Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, other race, and all respondents reporting more than one racial identification—have lower wealth than White families just higher wealth than Blackness and Hispanic families. The aforementioned patterns of inequality in the distribution of wealth across all families are also evident within race/ethnicity groups; for each of the four race/ethnicity groups, the mean is substantially college than the median, reflecting the concentration of wealth at the top of the wealth distribution for each group.

Figure 1. White families have more than wealth than Blackness, Hispanic, and other or multiple race families in the 2019 SCF.

The SCF data provide a snapshot of families' wealth at a indicate in fourth dimension. This point-in-time observation is a consequence of many complex societal, governmental, and private factors that play out over the life cycle and fifty-fifty across generations. Amidst other factors, inter-generational transfers, homeownership opportunities, access to revenue enhancement-sheltered savings plans, and individuals' savings and investment decisions contribute to wealth accumulation and families' financial security.4 In the remainder of this note, nosotros use the SCF to shed light on how these factors differ by race and ethnicity and how patterns in wealth-holding take inverse since the Great Recession.5 Before nosotros movement on, nosotros notation that families were primarily interviewed for the 2019 SCF before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated changes to the economy.6 Therefore, we urge readers to do caution in making any inferences based on the patterns described in this Note about how Usa families are faring in 2020.

Recent trends in wealth-holding

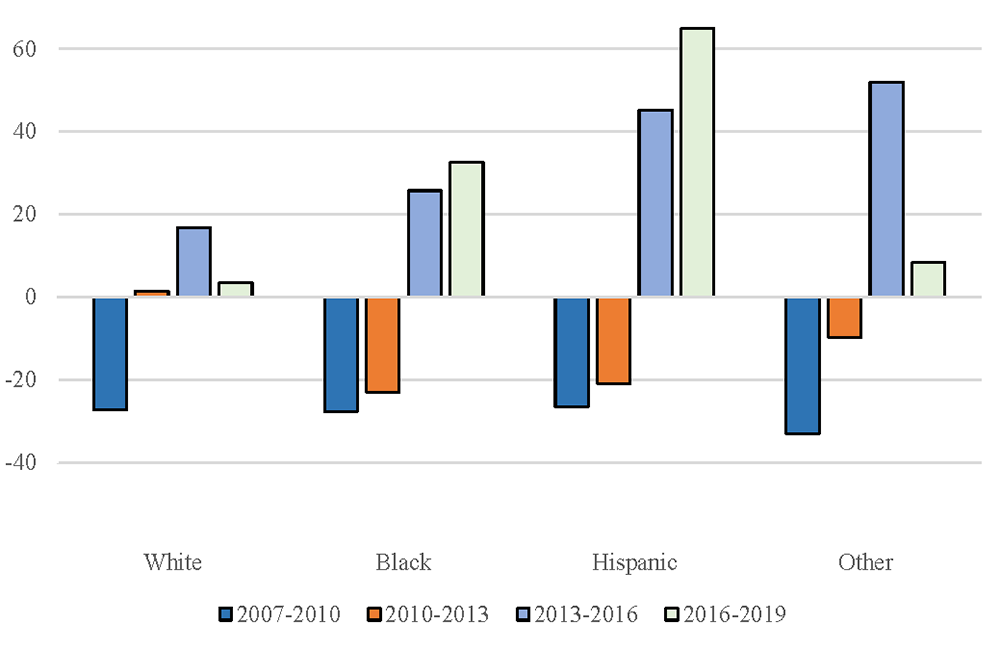

Between 2016 and 2019, median wealth rose for all race and ethnicity groups (Effigy 2). Growth rates for the 2016–xix period were faster for Black and Hispanic families, rising 33 and 65 percentage, respectively, compared to White families, whose wealth rose three per centum, and other families, whose wealth rose viii percent. That said, the faster growth in wealth for Black and Hispanic families only resulted in modest changes in the gaps in wealth between these families and White families. The White-Black gap in median wealth was little changed, from $163,700 in 2016 to $164,100 in 2019, and the White-Hispanic gap barbarous modestly from $160,000 in 2016 to $152,100 in 2019.

Figure 2. Blackness and Hispanic families experienced faster growth in wealth over the terminal 2 surveys afterwards experiencing larger declines in wealth caused by the Dandy Recession.

The patterns for the 2016-2019 period follow variation across groups in experiences in the Corking Recession (2007 to 2010), the immediate aftermath (2010 to 2013), and the continued economic expansion (2013-2019). Median wealth barbarous about 30 pct for all groups during the Great Recession. Notwithstanding, Black and Hispanic families' wealth continued to fall an boosted twenty per centum from 2010 to 2013, while White families' wealth was essentially unchanged, and other families' wealth fell a more modest 10 pct. After 2013, median wealth rose for all groups, with faster growth for Black, Hispanic, and other families.

Despite growth over the terminal ii surveys, the typical White family and the typical Blackness family unit have yet to recover to their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth. Over the unabridged 2007-2019 flow, wealth savage by 11 per centum for the typical White family and by 7 percent for the typical Blackness family. Only the typical Hispanic family has seen an increase in wealth relative to earlier the Peachy Recession, rise by about 39 percent, while the typical other family's wealth is almost unchanged since before the Great Recession.

While these cumulative changes in wealth from 2007-2019 may seem striking, there are two of import issues related to the interpretation of changes over time in the SCF from Figure ii, particularly over the total fourth dimension period.

First, the SCF interviews a unlike random sample of US families every three years. The same family does not appear in consecutive SCFs. Therefore, the appropriate interpretation of the survey-to-survey changes for a detail group, or cumulative changes over multiple surveys for a particular group, is virtually the typical (or average) family inside that group. The inappropriate interpretation is changes for a specific family over fourth dimension.

2nd, the types and number of families that make up each race or ethnicity grouping change over fourth dimension every bit the underlying population of United states of america families changes. Among other factors, population crumbling, changes to immigration flows, and the evolution of self-identification patterns alter the limerick of each race or ethnicity group betwixt surveys. For example, in the 2016 survey, the other or multiple race group was composed of l percent reporting more than i racial identification and 30 per centum reporting Asian, whereas in 2019 these figures inverse to 69 percent and 23 percent, respectively. Therefore, appropriately interpreting changes in a group's wealth, especially over longer time periods, requires acknowledging compositional shifts within each group. In particular, the robust growth in Hispanic wealth over the last two surveys and the marked slowdown of growth for other families in 2019 are at to the lowest degree partially attributable to compositional shifts in the types of families that make up these groups.

Wealth over the life-cycle

Wealth aggregating generally follows a predictable life-bike arc, wherein families mostly accumulate wealth during their working years, in preparation for retirement. Tabular array 1 displays median wealth by age category based on the age of the reference person, separately, for White, Blackness, Hispanic, and other families.vii Following the expected life-wheel savings patterns, within each race or ethnicity group median wealth is sharply higher for middle-aged families (35 to 54) compared to young families (under 35) and is highest amid older families (55 and over).

Table 1: Wealth rises with age for all families, merely substantial wealth gaps between White and non-White families persist throughout the life-wheel.

| White | Blackness | Hispanic | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 35 | 25.4 | 0.vi | 11.2 | 13.v |

| 35-54 | 185.0 | xl.1 | 46.one | 154.5 |

| Over 55 | 315.0 | 53.viii | 111.5 | 213.two |

Within each age group, the SCF data indicate large differences in wealth across racial and ethnic groups. Even among young families who accept had relatively little time to accumulate wealth, there are sizeable differences in wealth by race and ethnicity, well-nigh starkly betwixt young Blackness and young White families. The median young Black family has almost no wealth ($600). In contrast, the median immature White family has a wealth of $25,400. Young Hispanic and other families fall in between, with $11,200 and $13,500 in median wealth, respectively. Differences in parental resources may contribute to these early life cycle gaps, which we will discuss in the adjacent section.

In absolute terms, the gaps in median wealth between White and non-White families widen considerably at older ages. For example, amidst families under 35, White families have betwixt $11,900 and $24,800 more than in median wealth than Black, Hispanic, or other families. For families over historic period 55, the gaps widen to betwixt $101,700 and $261,100. In proportional terms, nonetheless, the gaps are relatively stable or diminish with historic period. With respect to the Blackness-White gap at middle and older ages, the median wealth of White families is four to 6 times greater than the median wealth of Black families. These within-age ratios are somewhat lower than the Black-White ratio of nigh 8 for all families combined (implied by Figure 1).

Inheritances and other family unit support

Wealth-property can differ beyond groups due to the intergenerational transmission of wealth. At that place are numerous ways families can transmit wealth and resources across generations. Families can direct transfer their wealth to the next generation in the form of a bequest. They can also provide the next generation with inter vivos transfers (gifts), for case, providing down payment support to enable a dwelling buy or a substantial wedding souvenir. By some estimates bequests and transfers business relationship for at least half of aggregate wealth (Gale and Scholz 1994), have recently averaged iii percent of total household disposable personal income (Feiveson and Sabelhaus 2018), and business relationship for more of the racial wealth gap than any other demographic or socioeconomic indicator (Hamilton and Darrity 2010).8 In addition to direct transfers or gifts, families can make investments in their children that indirectly increment their wealth. For example, families can invest in their children'south educational success past paying for college or private schools, which tin can in turn increase their children'due south ability to accrue wealth. For these reasons, wealth (or a lack thereof) can persist across generations and reflect, among other factors, a legacy of bigotry or unequal treatment in housing, instruction, and labor markets.9

Ane reason wealth-belongings is relatively loftier among White families is they are considerably more than likely to have received an inheritance or gift. Another reason is White families report other indicators associated with higher levels of family back up (Table ii). For example, nearly 30 per centum of White families report having received an inheritance or gift, compared to nigh 10 percent of Blackness families, vii percent of Hispanic families, and 18 percent of other families. Provisional upon receiving an inheritance or gift, White families besides tend to receive larger inheritances.

Table 2: White families are substantially more likely to receive inheritances, gifts and other family back up than Black and Hispanic families

| White | Blackness | Hispanic | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recieved an Inheritance (Percent) | 29.ix | 10.ane | 7.2 | 17.8 |

| Provisional Median Inheritance (Thousands of 2019 dollars) | 88.5 | 85.eight | 52.ii | 59.4 |

| Expect an Inheritance (Percent) | 17.1 | six.0 | 4.two | 14.seven |

| Conditional Median Expected Inheritance (Thousands of 2019 dollars) | 195.5 | 100.0 | 150.0 | 100.0 |

| Could get $iii,000 from family or friends (Percent) | 71.9 | 40.ix | 57.8 | 63.4 |

| Parent(southward) accept a College Degree (Per centum) | 34.4 | 24.eight | xv.2 | 40.0 |

Some families may not even so have received an inheritance (for example, if their parents are withal live), simply expect to receive 1 in the future. White families are both more than likely to accept received an inheritance and are also more likely to expect to receive an inheritance: about 17 per centum of White families look an inheritance, compared to vi percent of Black families, 4 pct of Hispanic families, and 15 percent of other families. Similarly, conditional upon expecting to receive an inheritance in the future, White families expect to receive relatively larger inheritances.

White and other families are more likely to written report other indicators associated with college levels of family unit back up. For instance, White and other families are considerably more likely to report existence able to obtain $three,000 from a family unit fellow member or friend in a financial emergency than Black or Hispanic families. They are also more probable to take a parent with a college degree. Since college levels of education are associated with higher levels of wealth (run across, for example, the Bulletin article), this association suggests White and other families are probable to accept wealthier parents than Black or Hispanic families.

Homeownership

For many families, housing is the biggest component of wealth. The relationship between housing and family unit wealth is complex. On the ane hand, the power to purchase a habitation is a reflection of wealth a family already has (or their parents' wealth, equally noted earlier), every bit meaning funds are generally required for a down payment and endmost costs. On the other hand, homeownership has also been plant to yield strong fiscal returns on average and to be a fundamental aqueduct through which families build wealth (Goodman and Mayer 2018).10

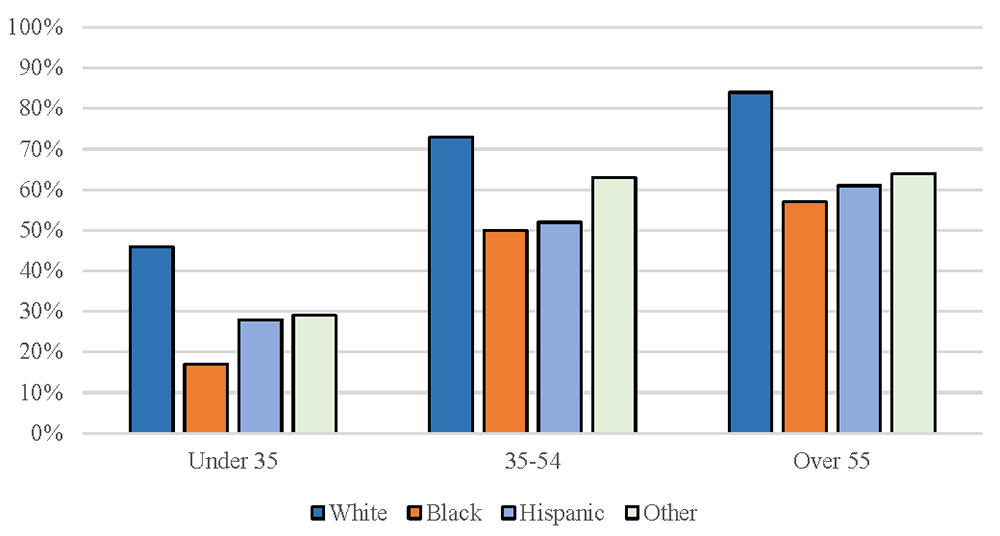

Life-cycle patterns of homeownership by age and by race and ethnicity are similar to the patterns of wealth (Figure 3). Homeownership rises sharply from immature to center-age regardless of race or ethnicity. At the same fourth dimension, within each age grouping there are significant gaps in homeownership between White and non-White families, with the biggest gaps betwixt White and Black families. Among young families, about 46 percent of White families own their dwelling house, compared to simply 17 percentage of Black families. This gap may partially reflect differences in parental wealth, as previous research has found that Blackness families are far less likely to receive downwardly payment assistance from their parents, delaying transitions into homeownership (Charles and Hurst 2002).11

Figure three. Homeownership rises with age regardless of race or ethnicity, though there are significant differences in homeownership between White and non-White families throughout the life-wheel.

This Black-White gap of most xxx percentage points narrows somewhat amongst middle-aged and older families. For example, 73 percent of middle-anile White families own their abode compared to virtually 51 percent of eye-aged Black families. Meanwhile, the gap in the homeownership rate between young White families and young Hispanic families is well-nigh 18 percentage points. In contrast to the White-Black gap, the White-Hispanic homeownership gap expands somewhat among middle-aged and older families.

In add-on to gaps in homeownership, there are also significant gaps in habitation values among homeowners by race and ethnicity. For homeowners, the typical White families' home value is $230,000 and the typical other families' domicile value is $310,000. The typical Black and Hispanic families' home values are lower, at $150,000 and $200,000, respectively. Gaps in home values are acquired both by gaps in purchase prices and housing appreciation, which are a reflection of a combination of factors including resources gaps (e.yard., income and downwardly payments), residential segregation, and age of entry into homeownership.12

Retirement accounts and plan participation

Participation in retirement accounts and retirement plans is another of import channel through which families build wealth, and they provide financial security in retirement. These assets include individual retirement accounts (IRAs), which typically are not dependent on a family'southward employer, and two types of employer-sponsored plans: divers contribution plans (DC), which are account-type job pensions such as 401(k)south, and traditional pensions (defined benefit plans, DB). Avails held in IRA and DC account plans are subject to preferential tax treatment, and DB plans guarantee a stream of income in retirement.

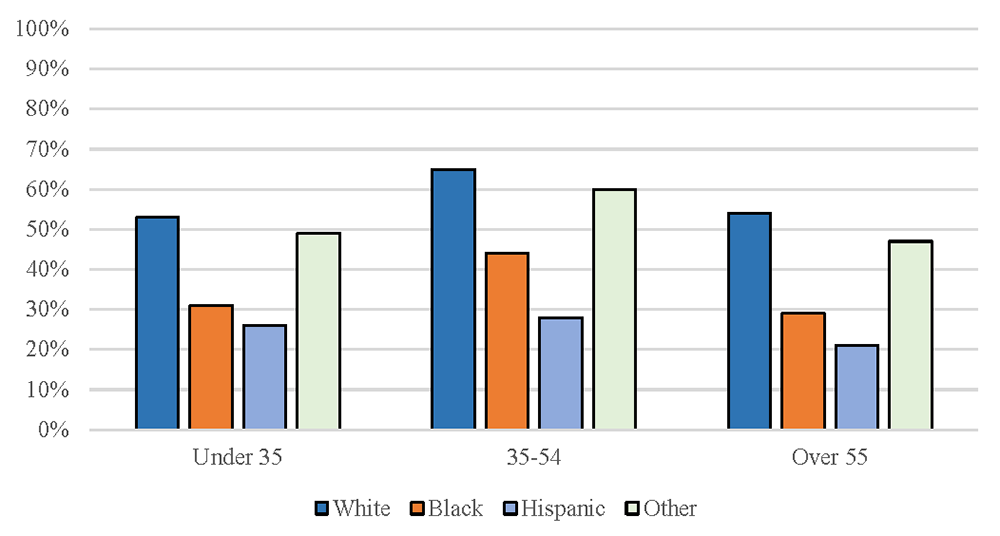

Ownership of IRA and DC retirement accounts rises among middle-aged families and then falls amidst older families (Figure 4). In all age groups, Black and Hispanic families are far less likely to take such retirement accounts. For case, among middle-anile families –who have the highest rates of account ownership— 65 percent of White families take at least one retirement account, compared to 44 percent of Blackness families, and just 28 pct of Hispanic families.

Effigy four. Retirement account ownership peaks at middle age, though ownership is less probable for Black and Hispanic families at all ages.

One reason for gaps in participation in retirement accounts is that not all families are eligible to participate in an employer-sponsored retirement program. Families may not be eligible for an employer programme considering their employer does not offer plans at all or they are offered but the employee is not eligible (for example, because the employee works part fourth dimension or the employee has bereft tenure at the company). Families who lack access to employer-sponsored plans miss out on a mutual added benefit: many employers contribute to these plans, either past matching some or all of the employee's contributions to the plan in the case of DC plans or by providing employees a guaranteed income stream in retirement for DB plans.

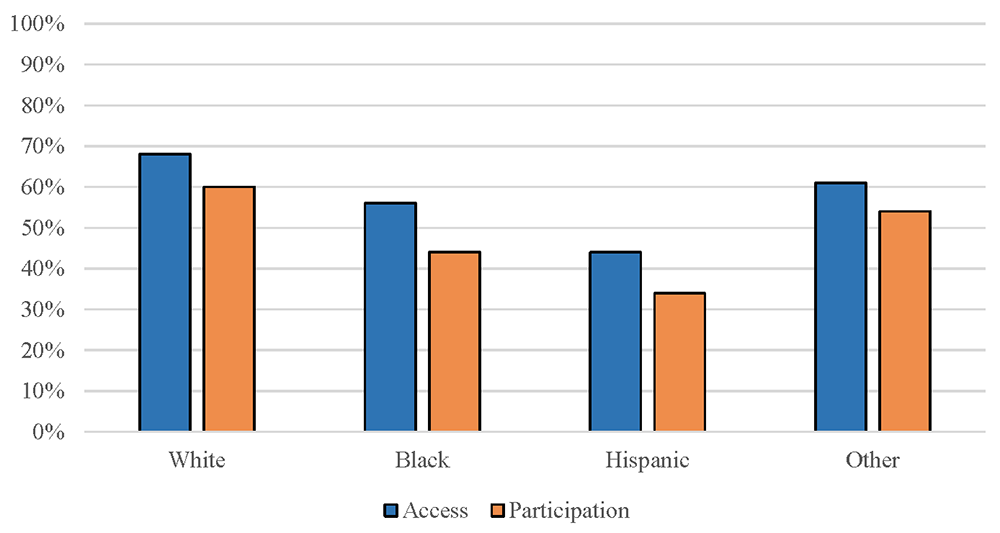

Among working-age families (those under age 55), White families and – to a lesser extent other families – take more widespread access to employer-sponsored retirement plans than Black or Hispanic families (Figure 5, blue bars).13 The disproportionate access for White families relative to Hispanic families is the well-nigh stark – for every three White families that can access an employer-sponsored retirement programme only two Hispanic families have access.

Figure 5. White and other or multiple race families have broader access and participate more in employer-sponsored retirement plans.

Even for those families with admission to an employer-sponsored plan, not all families opt to participate in a plan. For working-age families, participation rates are lower than admission rates (Figure 5, orange confined). About sixty percent of White and 54 percent of other families participate in a retirement programme, compared to 45 percent of Black families and 34 pct of Hispanic families. The share of each group that participates among those with admission –also known every bit the "take-up" charge per unit—also varies across groups. In addition to having higher rates of access, take-up rates are higher amid White and other families than Black or Hispanic families. While about 90 per centum of White and other families with admission to a plan participate, about 80 percent of Black families and about 75 percent of Hispanic families with access to a plan participate (implied past Figure 5). These differences in participation may be caused by a multifariousness of factors, including whether or non a family has sufficient income to enable saving in this manner, the types of funds offered by employer-sponsored plans, whether participation is by default or non, and financial literacy.

IRA and DC plans tin can only provide financial security in retirement if families accumulate sufficient balances in the plans through investment contributions and subsequent returns on those contributions. Amongst working-historic period families, balances in retirement accounts also vary by race and ethnicity, and balances are larger amongst groups with higher rates of access and participation. For working-age families that accept balances in such accounts, the typical White family has about $l,000 saved, which is two and a half times the amount saved equally the typical Black or Hispanic family, who have about $20,000 saved in retirement accounts. The median balances for other families falls in between White and Black or Hispanic families, at nigh $34,000. Departure in balances likely reverberate a combination of factors including differences in returns from the funds that contributions are invested in, differences families' lifetime contributions to retirement accounts, and differences in employer matching to DC plans. For example, the differences in access to employer-sponsored plans (Figure v) imply that fewer Black or Hispanic families are eligible for a plan with an employer match.

Overall, these gaps in retirement plan access, participation, and account balances suggest non-White families will exist less financially secure in retirement than White families. But our discussion ignores Social Security benefits and the net nowadays value of DB plans, which are central components of many families' retirement planning. These benefits are difficult to account for because they involve assumptions about families' future earnings and years of work. Withal, research suggests that bookkeeping for these benefits can reduce overall inequality in retirement resource (Bricker, Goodman, Moore, and Volz, 2020; Sabelhaus and Volz, forthcoming).xiv

Emergency Savings

Families often aim to build up easily-accessible savings to help deal with unexpected expenses and disruptions to their income. Although involvement rates on highly-liquid transaction accounts are generally quite low and, as a issue, these highly-liquid accounts are less important for long-term wealth-building than higher-return assets like housing or retirement accounts, savings can assist families avoid plush borrowing or missed payments when unexpected events arise.

Nearly all families have some type of highly-liquid asset, such as a checking account, savings account, or pre-paid card (Table three). Conditional upon having a liquid nugget, yet, the typical White family has considerably more liquid savings than the typical Black, Hispanic, or other family. While the typical Black or Hispanic family unit has $2,000 or less in liquid savings, the typical White family has more than iv times that amount. Other families fall somewhere in the heart, with the typical family property $5,000 in liquid savings.

Tabular array 3: White families have more emergency savings than Black or Hispanic families.

| White | Black | Hispanic | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has Liquid Assets (Per centum) | 98.8 | 96.8 | 95.5 | 98.viii |

| Conditional Mean Liquid Assets (Thousands of 2019 dollars) | 8.ane | one.5 | 2.0 | v.0 |

| Has Direct or Indirect Equity (Pct) | 60.8 | 33.5 | 24.2 | 53.eight |

| Conditional Median of Equities (Thousands of 2019 dollars) | 50.6 | xiv.4 | xiv.9 | 28.eight |

Families may also choose to tap into higher-return assets in a financial emergency, such as money stored in directly or indirectly-held equities. These assets include directly-held stocks and mutual funds, which tin be sold, and equities held in quasi-liquid accounts (such as retirement accounts), which tin be liquidated or borrowed confronting if a financial emergency were to occur.

There are substantial disparities in ownership of equities beyond families grouped by their race and ethnicity. While more than half of White and other families accept equities, just over 24 percent of Hispanic families and merely under 34 percent of Black families have any equities. Conditional on having equities, there are too substantial gaps in amounts held. For example, the typical White family has $50,600 in equities they could tap into in an emergency, compared to merely $14,400 for the typical Black family and $14,900 for the typical Hispanic family.

These gaps in emergency savings are especially relevant in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated job losses. Because the 2019 SCF data were collected simply before the onset of the pandemic, these gaps in savings suggest large disparities in families' power to atmospheric condition the pandemic. Indeed, Bhutta, Blair, Dettling, and Moore (2020) find that without the substantial cash assistance included in the Coronavirus Help, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, at that place would be large disparities by race and ethnicity in the share of families who could embrace their normal, recurring expenses if they were to lose their job for six months or more.15 They discover that just 10 percent of Hispanic families and 14 percent of Black families accept plenty savings to cover six months of expenses, compared to 36 percent of White families and 27 percent of other families. But with the greenbacks assistance in the CARES Act (i.e., unemployment insurance and direct stimulus payments), over 90 percent of all family-groups could embrace their expenses for six months. Still, much of the CARES Deed has expired or will expire in the coming months. If job losses persist, then unequal levels of savings could lead to disparities by race or ethnicity in fiscal distress during the pandemic. Furthermore, growing bear witness suggests Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities are existence disproportionally affected by the health and economic effects of COVID-19.16

Please cite this note as:

Bhutta, Neil, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne Westward. Hsu (2020). "Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 28, 2020, https://doi.org/ten.17016/2380-7172.2797.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are manufactures in which Lath staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These manufactures are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.

Source: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm

0 Response to "Of 20 Times More Wealth Between the Average White Family and the Average Black Family"

Post a Comment