What Is One of the Biggest Issues in Regard to Perpetuating Criminal Activities in Texas

Home Page > Publications > Detaining the Poor: How coin bail perpetuates an endless wheel of poverty and jail time

Detaining the Poor:

How money bail perpetuates an countless bike of poverty and jail time

Past Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf Tweet this

May 10, 2016

Press release

Print/PDF version

In addition to the 1.6 million people incarcerated in federal and state prisons, at that place are more than 600,000 people locked upward in more 3,000 local jails throughout the U.South. Over 70 percent of these people in local jails are beingness held pretrialone — meaning they have not yet been convicted of a criminal offence and are legally presumed innocent.2

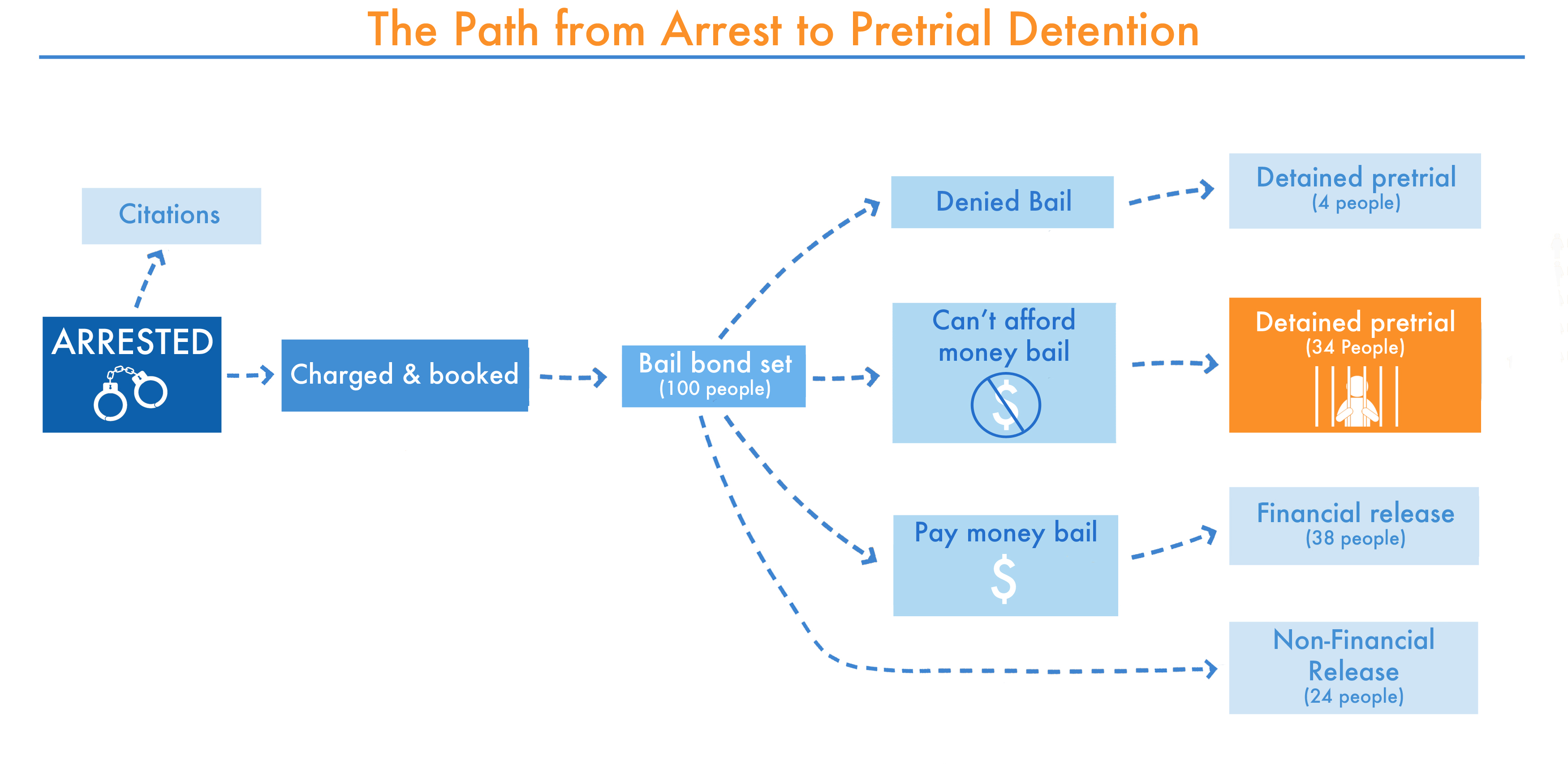

One reason that the unconvicted population in the U.S. is so big is because our state largely has a organization of money bail,3 in which the ramble principle of innocent until proven guilty only really applies to the well off. With money bail, a accused is required to pay a sure corporeality of money as a pledged guarantee that they will attend future courtroom hearings.4 If the accused is unable to come up upwards with the money either personally5 or through a commercial bail bondservant,6 they can be incarcerated from their arrest until their case is resolved or dismissed in courtroom.7

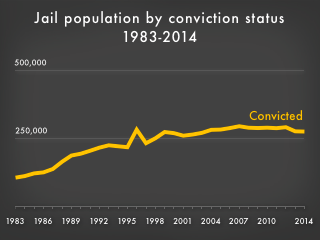

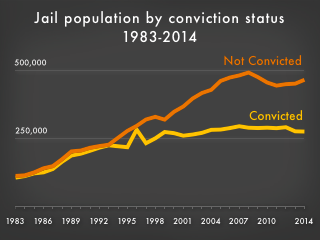

While the jail population in the U.S. has grown substantially since the 1980s, the number of convicted people in jails has been flat for the last 15 years. Detention of the legally innocent has been consistently driving jail growth, and the criminal justice reform discussion must include a discussion of local jails and the need for pretrial detention reform. This report will focus on one driver of pretrial detention: the inability to pay what is typically $10,000 in money bail.nine Building off our July 2015 study on the pre-incarceration incomes of people in prison, this report provides the pre-incarceration incomes of people in local jails who were unable to mail service a bail bond. This study aims to stimulate a more informed word about whether coin bail makes sense, given the widespread poverty of the people held in the criminal justice system and the high fiscal10 and social costs of incarceration, and offers recommendations for how states and counties can motion beyond unnecessary pretrial detention.

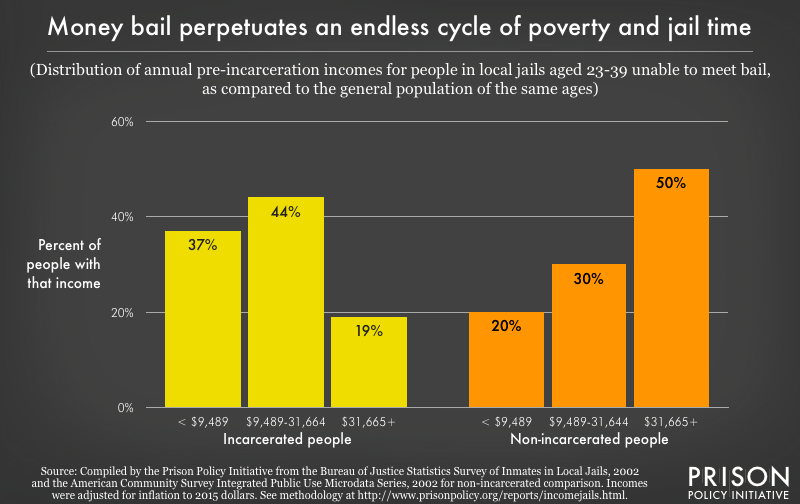

Nosotros observe that most people who are unable to meet bail autumn within the poorest third of society.11 Using Agency of Justice Statistics data, we find that, in 2015 dollars, people in jail had a median annual income of $15,109 prior to their incarceration, which is less than half (48%) of the median for non-incarcerated people of similar ages.12 People in jail are even poorer than people in prisonthirteen and are drastically poorer than their non-incarcerated counterparts.

| People in jail unable to see bail (prior to incarceration) | Not-incarcerated people | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| All | $15,598 | $xi,071 | $39,600 | $22,704 | |

| Black | $eleven,275 | $9,083 | $31,284 | $23,760 | |

| Hispanic | $17,449 | $12,178 | $27,720 | $14,520 | |

| White | $eighteen,283 | $12,954 | $43,560 | $26,136 | |

Effigy 2. Median annual pre-incarceration incomes for people in local jails unable to post a bond bond, ages 23-39, in 2015 dollars, by race/ethnicity and gender. The incomes in red fall below the Census Agency poverty threshold. The median bail bail amount nationally is almost a full year's income for the typical person unable to post a bail bond.

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| All | 61% | 51% |

| Blackness | 64% | 62% |

| Hispanic | 37% | sixteen% |

| White | 58% | 50% |

Effigy 3. Percentage divergence between the median pre-incarceration almanac incomes for people in local jails unable to post a bail bond and non-incarcerated people, ages 23-39, in 2015 dollars, by race/ethnicity and gender.

Unsurprisingly, white men have the highest incomes before incarceration while Black women have the lowest incomes earlier incarceration. The difference for Black men is particularly dramatic. Blackness men in jail have a pre-incarceration median income 64% lower than that of their non-incarcerated counterparts.

Examining the median pre-incarceration incomes of people in jail makes it articulate that the organisation of coin bond is set upwards then that it fails: the power to pay a bond bond is incommunicable for too many of the people expected to pay it. In fact, the typical Blackness man, Black woman, and Hispanic woman detained for failure to pay a bond bond were living below the poverty line earlier incarceration. The income data reveals just how unrealistic it is to look defendants to be able to quickly patch together $10,000, or a portion thereof, for a bail bond. The median bail bond corporeality in this state represents eight months of income for the typical detained defendant.

Effigy iv. People in local jails unable to meet bond are concentrated at the everyman ends of the national income distribution, particularly in comparison to non-incarcerated people. Every bit this graph shows, 37% had no take chances of beingness able to afford the typical amount of coin bond ($ten,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.

Effigy iv. People in local jails unable to meet bond are concentrated at the everyman ends of the national income distribution, particularly in comparison to non-incarcerated people. Every bit this graph shows, 37% had no take chances of beingness able to afford the typical amount of coin bond ($ten,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.

Because a system of money bond allows income to exist the determining factor in whether someone can exist released pretrial, our nation'south local jails are incarcerating too many people who are probable to show up for their court date and unlikely to be arrested for new criminal activity. fourteen Although, on paper, it is illegal to detain people for their poverty, such detention is the reality in too many of our local jails. Our country at present has a two-track system of justice in which the cost of pretrial liberty is far higher for poor people than for the well off.

Recommendations

This study shines light on another injustice of the American criminal justice system — the unnecessary and excessive detention of poor people in our local jails. To truly make our local communities safer and ensure that bail decisions are based on more than how much money ane has, states, local governments, and sheriffs should:

-

Eliminate the employ of money bond

Too many jails are detaining people not because they are unsafe, merely because they are too poor to beget bail bonds. One study of felony defendants nationwide found that an additional 25% percent of defendants could be released pretrial without any increases to pretrial criminal offence. The written report found that many counties could safely release older defendants, defendants with clean records, and defendants charged with fraud and public order offenses, all without threatening public safety.At a fourth dimension when the White House is condemning coin bond as "a rough way to screen pretrial defendants for their risk of flight or to the community," states and local governments should eliminate money bail. Instead, courts tin increase their apply of non-financial forms of pretrial release such equally release on own recognizance, which is when a defendant signs an agreement that he will appear in court equally required and is non required to pay any coin for pretrial release.15 Some other selection is to apply unsecured bondsxvi instead of money bond. Through unsecured bonds, a defendant is not required to pay any money to be released pretrial, but he volition exist liable to pay an agreed upon amount of money if he does not appear for courtroom. Unsecured bonds are as constructive at achieving public condom and court appearance as money bond and much more effective at freeing up jail beds. States and local governments interested in eliminating coin bail tin can follow the atomic number 82 of Kentucky and the Commune of Columbia. Kentucky banned for-profit money bond 40 years ago, and a statewide agency instead uses a risk assessment tool17 to determine who will be released pretrial. In D.C., about defendants are released on ain recognizance, during which time they are supervised by the D.C. Pretrial Services Bureau.18 Both Kentucky and D.C. have remained successful at ensuring defendants show up for court and avoid abort for new criminal activeness.

-

End locking people upward for failure to pay fines and fees

As the criminal justice system and its associated costs take grown, states and local governments such as Ferguson, Missouri have adopted a misguided policy: charging defendants fines and fees to pad their correctional, and even municipal, budgets.19 Because, as this report shows, the people who are being charged these fines and fees are largely poor, states and local governments unsurprisingly have difficulty collecting these funds20 and, for failing to pay criminal justice debt, people can country in jail. For instance, in Rhode Island in 2007, 18% of defendants were locked up for criminal justice debt.States and local governments should stop locking people up for failure to pay criminal justice debt that they cannot beget, a practice repeatedly deemed unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.21 If states and local governments decide that charging fines and fees is worth the effort, they should consider ability to pay when assessing fines and fees and be flexible past assuasive payment plans, community service in lieu of payment, and exemption waivers for poor defendants. For instance, in 2011, Washington State passed legislation permitting waivers of involvement that is accrued on criminal justice debt while a person is locked up. After researching the net gains of fee collections, Leon County, Florida decided to close its Collections Courtroom and terminated thousands of outstanding arrest warrants.

-

Reduce the number of arrests that lead to jail bookings through increased use of citations and diversion programs

Despite falling crime rates, the likelihood of arrest has increased modestly for violent and property crimes and dramatically for drug crimes over the by three decades.22 More arrests hinder criminal justice reform by increasing the number of people locked upward in the U.S. By choosing to lock up people who need mental health and substance apply services and not jail time, American jails have become de facto mental health institutions.1 of the all-time nevertheless underused reforms bachelor to our local criminal justice systems is for law to reduce the number of arrests that atomic number 82 to jail bookings. Instead, police can cite23 people and so that defendants tin wait for their court engagement at home without having to mail money bail or hazard losing employment. Kentucky, Maryland, and D.C. take all increased their utilise of citations. States and local governments can also follow the pb of Seattle, which implemented Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD). Through Lead, constabulary officers connect people — who are often battling chronic homelessness, substance utilise, and mental health challenges — to social services rather than bringing them to jail. Atomic number 82 has been constructive at both reducing arrests and slowing the rate at which people arrested for low-level crimes bike through Seattle jails.

-

Increase funding of indigent criminal defense

Almost defendants are likewise poor to afford a private attorney to represent them. Further, while the Supreme Court has affirmed the ramble right to counsel at initial appearance,24 in reality, only ten states and D.C.25 provide counsel at initial appearance. A study of defendants in Baltimore institute that the failure to provide legal representation when bail bonds are determined was a leading reason for lengthy pretrial detention. Defendants who were represented had a median jail stay of two days while unrepresented defendants had a much longer median jail stay of 9 days.Greater funding of indigent criminal defense is imperative to making sure that incarceration is but used when necessary and that the sentence is proportional to the offense. Increased funding could ensure both that the right to counsel is the reality for even the poorest defendants and that more defendants have the guidance of an attorney earlier in the legal process, such every bit when the bond bond amount is gear up or reviewed. One contempo example is in San Francisco, where the public defender's office has assembled a Bail Unit of measurement. Comprised of two lawyers, ii paralegals, and interns, the Bail Unit of measurement works to contest bail bonds for nearly all of the public defender'due south clients.

-

Eliminate all pay-to-stay programs

Jails and prisons in forty-1 states charge incarcerated people for room and board through pay-to-stay programs. For instance, Riverside County, California requires incarcerated people to pay $142 per twenty-four hour period for their incarceration. At present that the data in this report can confirm that the majority of people that fill our local jails are poor, states and local governments should resist the temptation to create new forms of criminal justice fees, such equally increasingly common pay-to-stay programs. Otherwise, states and local governments run a risk spending more on the administrative costs of drove than the petty coin they are able to hunt down. In 2013, Riverside County had collected less than 1% of what it hoped to generate through its pay-to-stay programme.If states and local governments insist on having a pay-to-stay program, they should, at the very to the lowest degree, make certain to research the likelihood that a programme would exist worth information technology before implementation. For example, when a committee was formed in Massachusetts to consider whether introducing a room and board fee in prisons and jails would feasibly increase revenue, the committee ended that the harms of boosted fees outweighed the benefit.

-

Reduce the high costs of telephone calls home from prisons and jails and stop replacing in-person jail visits with expensive video visitation

Telephone calls home from prisons and jails and increasingly common remote video visits typically toll $1 per minute. The high prices of these communications products act like a regressive tax, charging the people who accept the to the lowest degree the most to continue in touch. As a outcome, more than than a third of families of incarcerated people fall into debt to comprehend phone and visitation costs. And it is these aforementioned family members who defendants oftentimes turn to when trying to scrape together money for bond bonds26 or other criminal justice fines and fees.While the Federal Communications Committee has been working to protect incarcerated people and their family unit members from these high costs, a federal court has stayed parts of the FCC's final round of regulations. States and local governments should not wait around until the lawsuit is resolved. Instead, they should follow the lead of many states such as New York and, recently, Mississippi by immediately reducing the rates in their phone and video visitation contracts. States and local governments should besides protect the in-person visitation rights of people in local jails and resist the temptation to supplant complimentary in-person visitation with expensive computer chats. Recognizing how video visitation is cost-prohibitive for many families, the state of Texas as well every bit Multnomah County, Oregon and Alameda County, California accept all protected in-person visitation rights for people in local jails.

Methodology

Background

This is not the first study to address the incomes of incarcerated people. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) collects this data periodically (near recently in 2002 with another survey scheduled to begin in 2018) just does not routinely publish the results in a format that can be accessed without statistical software. The BJS last published a complete analysis of the survey results in 2004. Last year, nosotros produced a report on the pre-incarceration incomes of people in state prison. This written report focuses on the pre-incarceration incomes of people in local jails, and, even more specifically, on the incomes of people incarcerated in local jails who had the opportunity to post bail, but could not meet information technology. This report included both convicted (people who were detained for the entire pretrial period so sentenced to jail time) and unconvicted people because only looking at the unconvicted population detained pretrial would take been too small of a sample size.

This report was non intended to make the point that incarceration causes poverty, although at that place is extensive research on that topic. Because the Prison Policy Initiative is regularly asked about the office that poverty plays in who ends upwardly backside bars, this study is aimed at answering a different question: are incarcerated people poorer than not-incarcerated people? In particular, we often hear that lxxx% of defendants nationwide are indigent, just we wanted to be able to put numbers to the trouble in the hopes of furthering the conversation on the growth of pretrial detention and the urgent need for bail reform.

To exist articulate, this study relies on the Bureau of Justice Statistics survey from 2002, which is both quite old and the newest bachelor. While we look forward to the Agency of Justice Statistics administering a survey in 2018, information technology will take a few years before that information is published, and nosotros know of no reason or trend that would make relying on the 2002 survey less reliable than the alternatives of using information that is even older or no data at all.

Further research should wait at the furnishings of educational attainment and prior prison or jail time on the pre-incarceration incomes and identify policies that could address those disparities.

Data sources and process

This report is the result of a collaboration betwixt Bernadette Rabuy, Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative, and data scientist and journalist Daniel Kopf, who is also a member of our Lath of Directors.

Together, we studied the BJS Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002 relying in particular on the questions listed below and then developing a manner to make the information comparable to non-incarcerated people.

- S7Q11c. Which category on this card represents your personal monthly income from ALL sources for the calendar month before your arrest?

- S1Q1a. Sex

- S1Q2a. What is your date of birth?

- S1Q3a. Are you of Spanish, Latino, or Hispanic origin?

- S1Q3c. Which of these categories describes your race?

- S3Q3a. At any time after your arrest for the…accuse(s) was bail or bond set?

- S3Q3c. Were y'all released on bail or bond?

The non-incarcerated data comes from the Census Agency's American Community Survey (ACS), specifically from the Integrated Public Apply Microdata Series (IPUMS). We used information from 2002 both because this was the same year as the incarcerated survey data, and because the ACS in 2002 included only people in households and did not include jails and other grouping quarters.

Because income is correlated with age and because the incarcerated population trends younger than the general U.S. population, we thought it would be well-nigh authentic to compare people of similar ages. We limited our study to the 25th and 75th percentiles of ages for incarcerated people (ages 23–39), and we used the same age range for the non-incarcerated population.

To make all of this information more than accessible and useful, nosotros converted all information in ii ways: We converted monthly incomes to annual incomes by multiplying by 12, and we multiplied each income by i.32 to adjust for inflation from 2002 to 2015, as provided past the Agency of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Reckoner. (We chose to adjust to 2015 dollars instead of 2016 because the 2016 index value volition change from month to month. Considering 2016 is not however over, the 2016 index value is based only on the latest monthly values.)

In improver, to provide an estimated median income for each incarcerated race/ethnicity/gender group from the BJS "grouped frequency" data, we followed these steps:

- Take the distance betwixt the smallest and largest number in the group containing the median

- Multiply this number past the following: ( ( (full data points/ii) - total data points in groups with lower numbers) / data points in group containing median )

- Add everyman number in group containing the median

On definitions

Notation that throughout this report, the incomes for incarcerated people are the incomes incarcerated people reported earning before their arrest, not the incomes they earned through work programs backside bars. For incarcerated people and non-incarcerated people, incomes include welfare and other public assistance. For incarcerated people, incomes also include illegal sources of income.

We use "Not-incarcerated" to refer to people in households, and thereby exclude people in group quarters, including people in correctional facilities, psychiatric hospitals, college/university housing, or residential handling facilities.

Our data on "Blacks" and "Whites," relies on data for Non-Hispanic Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. The federal government defines Blackness and White as races while Hispanic is divers as an ethnicity (and, therefore, it is possible to place as both Hispanic and White or Hispanic and Black). Our data for both incarcerated people and non-incarcerated people allowed us to avert overlap past separately talking almost Not-Hispanic Whites, Not-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics.

Appendix

The 2002 BJS survey asked incarcerated people what their personal monthly income was the month before their arrest. Get-go, the information in this appendix is presented in monthly incomes and has not been adjusted for inflation. Second, the information in this appendix is presented for people in local jails in general. In this report, we focus on the people in local jails who had the opportunity to be released pretrial but were unable to see the conditions of bail.

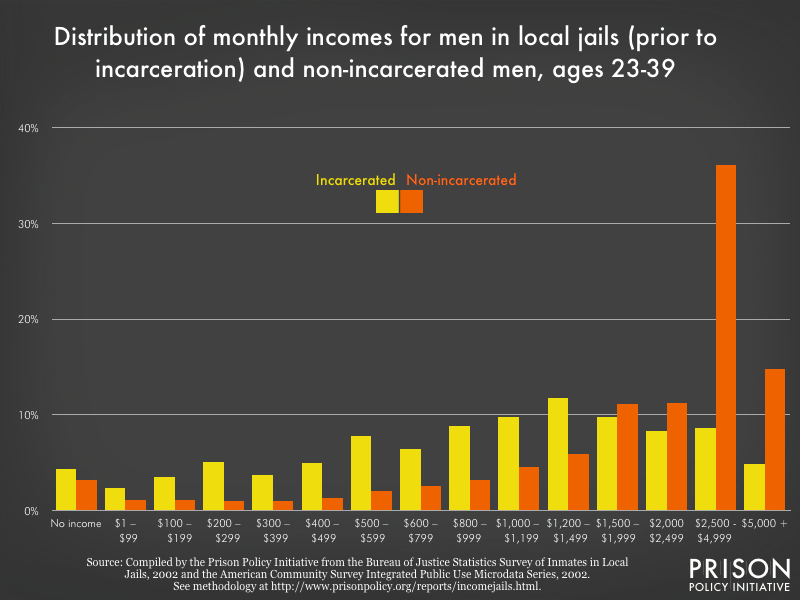

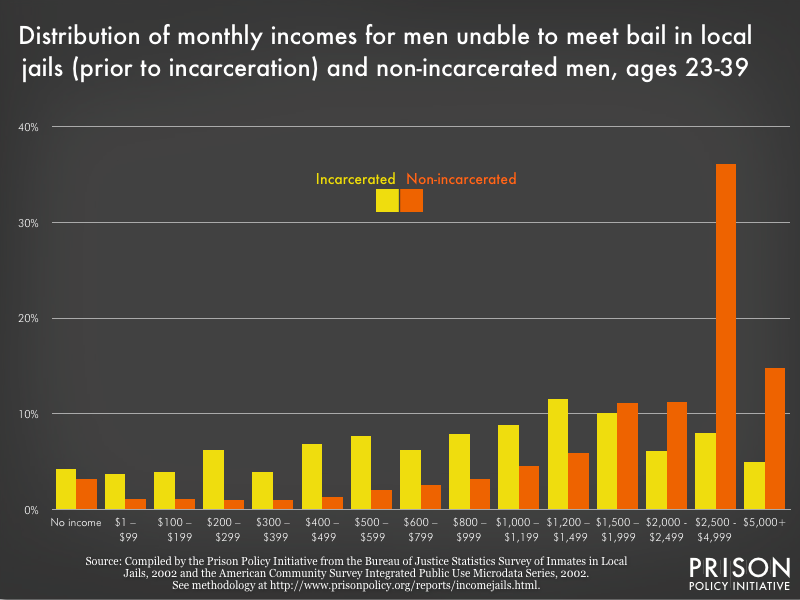

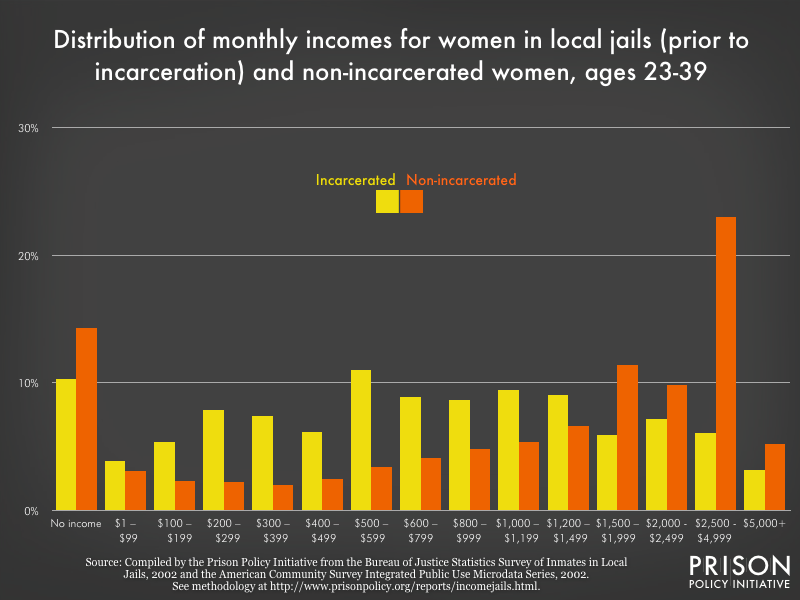

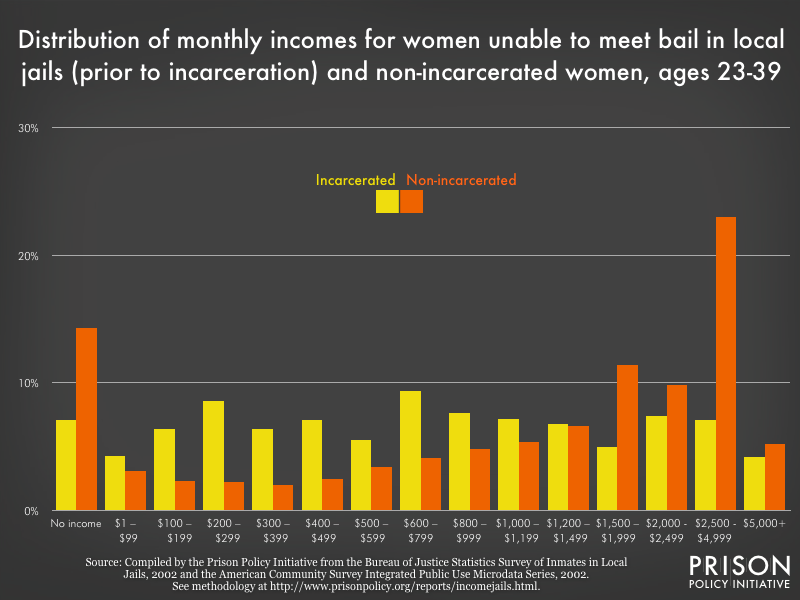

The following tables and graphs allow for comparisons between the incomes of incarcerated people prior to incarceration and the incomes of non-incarcerated people for each of the income categories that BJS provides respondents in its Survey of Inmates in Local Jails. The graphs also show that incarcerated people are dramatically full-bodied at the lower ends of the national income distribution.

| People in jails (prior to incarceration) | Non-incarcerated people | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| All | $i,061 | $671 | $2,500 | $i,433 | |

| Black | $900 | $568 | $one,975 | $one,500 | |

| Hispanic | $1,114 | $709 | $1,750 | $917 | |

| White | $1,236 | $813 | $ii,750 | $1,650 | |

Figure v. Median monthly pre-incarceration incomes for people in local jails, in 2002 dollars, ages 23-39, past race/ethnicity and gender.

Effigy half-dozen. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for men in local jails and non-incarcerated men, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

Effigy half-dozen. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for men in local jails and non-incarcerated men, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

Effigy vii. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for men unable to run across bond and non-incarcerated men, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

Effigy vii. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for men unable to run across bond and non-incarcerated men, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

| Income category | Proportion of men in local jails with that income (prior to incarceration) | Proportion of men unable to meet bail with that income (prior to incarceration) | Proportion of not-incarcerated men with that income |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0 | iv.37% | 4.21% | 3.22% |

| $1-99 | 2.35% | 3.71% | 1.13% |

| $100-199 | 3.48% | 3.92% | 1.06% |

| $200-299 | 5.04% | 6.17% | 0.95% |

| $300-399 | 3.75% | iii.9% | 0.96% |

| $400-499 | 4.99% | half-dozen.82% | ane.26% |

| $500-599 | 7.79% | 7.71% | 2.02% |

| $600-799 | half-dozen.44% | six.22% | 2.60% |

| $800-999 | eight.81% | 7.9% | 3.22% |

| $one,000-1,199 | ix.78% | 8.75% | 4.45% |

| $1,200-1,499 | 11.70% | 11.47% | 5.88% |

| $i,500-i,999 | 9.72% | 10.08% | 11.08% |

| $2,000-ii,499 | viii.thirty% | half dozen.thirteen% | eleven.xviii% |

| $two,500-4,999 | 8.66% | 7.99% | 36.xv% |

| $5,000+ | four.82% | 5.01% | 14.84% |

Effigy 9. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for women in local jails and non-incarcerated women, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39. While most people in local jails make less prior to incarceration than people on the outside, there is one interesting bibelot in the information for women non present in the data for men. More non-incarcerated women study no income at all than incarcerated women prior to incarceration. For both groups, the reported incomes include wages, welfare, and other public assistance, only since these are private surveys, they do not include spousal income. It is likely that many of those non-incarcerated women with zero reported income are receiving back up from their spouses.

Effigy 9. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for women in local jails and non-incarcerated women, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39. While most people in local jails make less prior to incarceration than people on the outside, there is one interesting bibelot in the information for women non present in the data for men. More non-incarcerated women study no income at all than incarcerated women prior to incarceration. For both groups, the reported incomes include wages, welfare, and other public assistance, only since these are private surveys, they do not include spousal income. It is likely that many of those non-incarcerated women with zero reported income are receiving back up from their spouses.

Figure 10. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for women unable to run into bail and non-incarcerated women, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

Figure 10. Distribution of monthly pre-incarceration incomes for women unable to run into bail and non-incarcerated women, 2002 dollars, ages 23-39

| Income category | Proportion of women in local jails with that income (prior to incarceration) | Proportion of women unable to run across bond with that income (prior to incarceration) | Proportion of non-incarcerated women with that income |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0 | 10.27% | 7.13% | 14.3% |

| $ane-99 | 3.85% | four.29% | 3.one% |

| $100-199 | five.xl% | half-dozen.38% | 2.iii% |

| $200-299 | 7.89% | 8.57% | 2.2% |

| $300-399 | 7.39% | 6.37% | ii.0% |

| $400-499 | 6.sixteen% | seven.12% | 2.five% |

| $500-599 | ten.98% | v.45% | 3.iv% |

| $600-799 | eight.91% | nine.45% | 4.1% |

| $800-999 | 8.67% | 7.65% | 4.8% |

| $1,000-1,199 | 9.xl% | vii.15% | 5.iv% |

| $ane,200-one,499 | 9.02% | 6.81% | 6.six% |

| $ane,500-1,999 | v.89% | 4.99% | 11.iv% |

| $two,000-2,499 | seven.14% | 7.35% | 9.8% |

| $2,500-4,999 | 6.09% | seven.13% | 23% |

| $5,000+ | 3.21% | four.17% | 5.two% |

Acknowledgments

This report was fabricated possible cheers to the generous contributions of individuals across the country who back up justice reform. Effigy 1 and the jail population past convicted status blithe graph were made possible by Elydah Joyce and Jacob Mitchell of the organization'southward Young Professionals Network, respectively. Bob Machuga created the covers, and the residual of the Prison Policy Initiative staff helped the authors assemble inquiry. The authors would like to thank the Pretrial Justice Institute both for providing invaluable feedback on an early on draft of the study and the great work they do for pretrial justice. Any errors or omissions, however, are the sole responsibleness of the authors.

Well-nigh the authors

Bernadette Rabuy is the Senior Policy Annotator at the Prison house Policy Initiative. Bernadette produced the first comprehensive national written report on the video visitation industry, Screening Out Family unit Time: The for-turn a profit video visitation industry in prisons and jails, finding that 74% of local jails that adopt video visitation eliminate traditional in-person visits. Her research has played a key function in protecting in-person family visits in jails in Portland, Oregon and the land of Texas. In her other work with the Prison Policy Initiative, Bernadette has worked to empower the criminal justice reform movement with cardinal but missing information through the annual Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie reports also equally last year's report, Prisons of Poverty, which for the beginning time provided the pre-incarceration incomes of women in state prison. Bernadette is on Twitter at @BRabuy

Daniel Kopf is a data scientist in California and writer at Priceonomics who has been a fellow member of our Young Professionals Network since February 2015. He has previously written about bail and has co-authored several exciting statistical reports with the Prison Policy Initiative: Prisons of Poverty : Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned, Separation past Bars and Miles : Visitation in state prisons, and The Racial Geography of Mass Incarceration. He has a Masters in Economics from the London School of Economics. Dan is on Twitter at @dkopf

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/incomejails.html

0 Response to "What Is One of the Biggest Issues in Regard to Perpetuating Criminal Activities in Texas"

Post a Comment